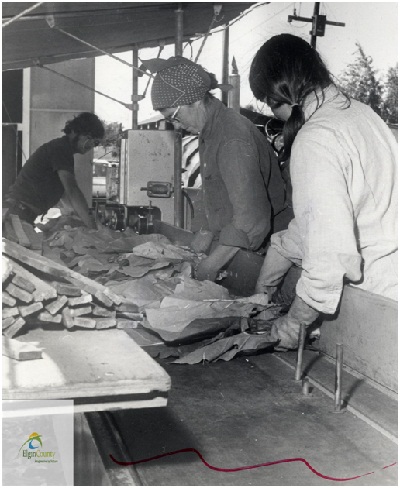

Into the Kiln

Workers on the tobacco farm of Andre Versnick, RR 2, Aylmer, are shown in August 1972 tying tobacco to be hung in kilns for curing. Pictured are Wendy Cosyns, foreground, of RR 1, Sparta; Mrs. Don Ashton of RR 2, Aylmer; and Heriberto Goertzen, a Mexican hired by Andre Versnick to help with that year's harvest.

St. Thomas Times-Journal fonds, C8 Sh2 B2 F5 26.

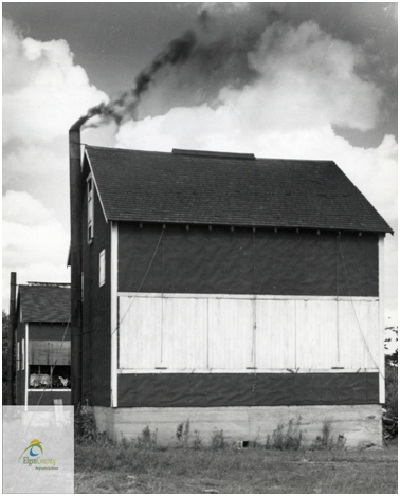

Early-August to Early-October

The job of tying leaves to slats used to be done by a table gang made up primarily of women, but by the 60s was mostly done by a machine which stitches the leaves together just above the slat. Labourers are still needed to place the leaves and slats into the machine for stitching. These slats are taken to the kilns for curing. Old-style kilns usually stand 14 to 16 feet high on a 22 X 24 feet foundation of cement. The interior consists of a network of hangers which allow tobacco slats to hang. A standard kiln will hold approximately 1,200 slats, each holding about 90 leaves. Modern bulk kilns use metal frames with rods, called racks, that pierce the tobacco leaf. The frames are then slid along metal runners to pack them into the kiln. Many tobacco farmers later upgraded to bin kilns.

Coal-fired kiln cures leaf on Alex Koyelaitis farm, Aldborough, in August 1956.

St. Thomas Times-Journal fonds, C8 Sh2 B2 F5 2f.

Tobacco in

Elgin County :

Production :

- Preparation

- Transplanting

- In The Field

- Harvest

- Into the Kiln

- Flue-Curing

- Baling

- Crop Damage

- The Workers